The Meditative Practice Behind Dimensional Collaging

Dimensional collage offers artists a unique way to work with time, space, and material memory. More than simply placing images onto a surface, this process invites deliberation, spatial awareness, and a deeper engagement with both the self and the subject. For many artists, it becomes a meditative practice—one that slows the tempo of creation and invites attention to the nuance of placement, texture, and meaning.

Understanding Dimensional Collaging as a Practice

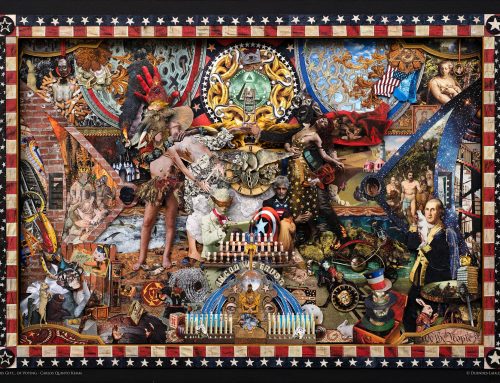

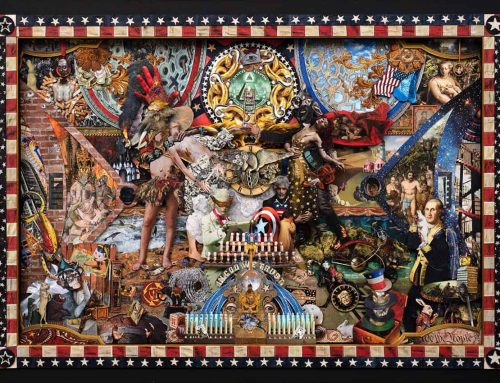

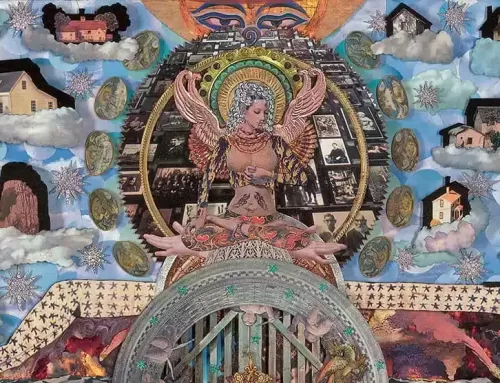

Unlike flat collage work, dimensional collaging builds upward, introducing physical depth and layered presence. Each element added changes the way light moves across the piece. The result is not merely visual—it’s temporal. The work exists across multiple moments, holding remnants of each decision in material form.

Attaching a raised photograph to a base of worn canvas, for instance, changes how that image is received. A slight crease might distort its shape; a warped corner may cast an unexpected shadow. These aren’t errors—they are quiet shifts in emphasis. They become the texture of the story.

This approach requires patience. Glue sets unevenly. Materials buckle or resist. The process demands time and a kind of listening. In that listening, clarity emerges. The artist becomes less focused on outcome and more aware of presence.

Creating Space for Thought Through Layering

Every material used in dimensional collage carries with it a residue of meaning. A rusted paperclip, a torn envelope, or a faded receipt—all of these fragments introduce their own histories. They are not passive elements. They assert emotional tone, suggest narrative direction, and influence the rhythm of composition through their texture, history, and placement. When layered together, they form not just a picture, but a dynamic system of meaning.

Layering slows the act of making. It invites reflection. Each decision—what to reveal, what to obscure—introduces both risk and opportunity. The artist begins to work less from a place of composition and more from a sense of relationship. What connects? What interrupts? What feels unresolved, and should remain so?

The process often surprises. Plans shift. Materials dictate. Collaging becomes not an imposition of vision, but a conversation with fragments.

Texture as a Tool for Presence

Texture plays a central role in dimensional collage. Rough burlap, crinkled tissue, peeling paint—these are not simply aesthetic details. They shape the viewer’s response and anchor the artist in tactile reality. Touch becomes a form of thought—a way of reasoning through material, where the pressure of the hand, the grain of paper, or the resistance of a thread quietly shapes the next decision before the mind catches up.

As the artist moves their hand across these surfaces, they move out of abstraction and into sensation. The tactile qualities of the piece pull attention into the present moment. A strip of linen doesn’t just lie flat—it tugs, folds, shifts. The thread unravels. The paper resists. Each detail slows the hand, and in doing so, focuses the mind.

This is where meditative practice begins—not through intention, but through absorption. The work demands presence, and the artist responds. This reciprocity gives the work its emotional resonance.

Contrast and TensionShifting Focus from Outcome to Process

In dimensional collage, resolution often arrives indirectly. The finished piece is rarely what was first imagined, often shaped by the resistance of materials, the evolution of emotional intent, or the quiet surrender to something unexpected emerging through the act of making. Instead, it becomes a record of interaction. Each fold, each adhered scrap, documents a moment of consideration.

Over time, artists come to value the act of making more than the final result. This shift mirrors mindfulness practices found in other disciplines. Like walking meditation or breathwork, collage invites return—to the hands, to the page, to the pause between decisions.

Control gives way to intuition. The artist stops trying to dominate the piece and begins to collaborate with it. This collaboration builds trust—not just in the work, but in the act of making itself.

A Practice That Builds Over Time

Like any contemplative process, dimensional collage develops slowly. Artists grow more fluent in the language of layering. They begin to notice smaller details: the way a yellowed tape edge interacts with a charcoal smear, or how the spacing between two torn papers changes the rhythm of the page.

Some begin without a defined goal. Others arrive with a framework, only to watch it dissolve. The process adapts to the moment, and in doing so, teaches the artist something about patience and flexibility. Work continues in the artist’s thoughts long after their tools are set aside. Collages are often solved in fragments—on a walk, in a dream, while staring at a blank corner of the studio wall. A decision about placement, unresolved in the moment, might find its answer in the curve of a vine glimpsed through a window or in the memory of how waxed paper once curled in a childhood kitchen drawer. These resolutions surface quietly, often long after the tools have been set aside.

This is not passive. It is integration. The work lives both on the table and in the body.

Why It Matters

Dimensional collaging offers more than a creative outlet. It provides a way to slow down in a culture that accelerates everything. It models care in place of efficiency. It rewards curiosity over perfection.

The lessons learned at the table often follow the artist into the rest of their life. They begin to notice more. To rush less. To trust the process—not just in art, but in conflict, in healing, in thought.

And in the end, there is a piece. Not just completed, but lived with. A collage that holds time as well as texture. One that honors emotion, imperfection, and attention. That is the quiet promise of the meditative practice behind dimensional collaging. Not to fix or impress, but to witness—and to feel what it means to be truly present in the making.