Contemporary Art in New Mexico

By Jan Adlmann with Barbara McIntyre

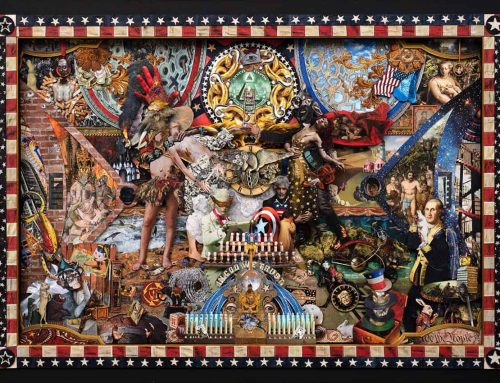

Anonymous Bosch, the very clever title of one group exhibition – among many – in which Carlos Quinto Kemm recently participated, is a terrific touchstone to this artist’s passing strange work. There’s most definitely a hint of the delightfully lunatic universe of Hieronymous Bosch in many of Kemm’s works. But, behind that irrational veil, there’s also a soupcon of Bosch’s perverse delight in representing delicious carnality, corruption and chaos. Often, Kemm, like Bosch, enshrines his little vignettes – little three-D theatrical tableaux, in fact – in an enchantingly bejeweled (and occasionally more than a trifle “dotty”) daintiness.

This kind of brilliant transmutation of passion is not unlike the gorgeous, enamel-like colors and intricate patterns of Persian miniature paintings, where fantastic myths and boudoir secrets alike become primarily excuses for a riot of great decor.

After recovering from the instant seductiveness of Kemm’s works, many art lovers ought to be transfixed not merely by their dizzying array of art historical quotations, but also by his highly considered, highly eclectic borrowings form a couple of very disparate traditions – from Byzantine mosaics to Coromandel screens, from books of hours to Peter Carl Faberge, from Gobelins to cloisonn‚. Kemm’s most successful work represents the rare reappearance (albeit hallucinatory) of a slender thread of preciousity running through the history of art. If we didn’t have Cellini, Renaissance art would be slightly diminished, for example, El Amor Brujo is a consummate fantasia by Carlos Kemm, not the least because he is once again drawn to a real penchant, an amour propre, i.e., Love, and the garden of earthly delights. That there is often a lingering scent, like patchouli, of San Francisco psychedelics about all this puts some off, but turns me on. What dreamy concoctions these are.

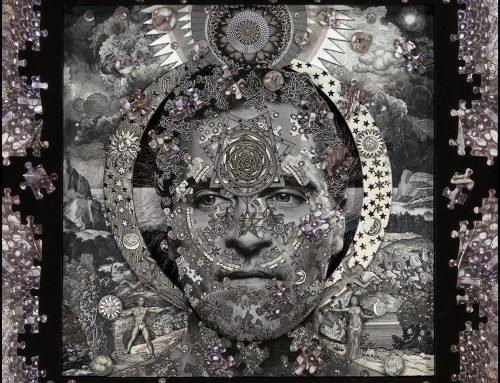

La Leyenda de la Luz, (the Legend of Light) – which looks, at first, like a detail from an especially trippy tanka – also illustrates the kind of grand subjects Kemm is inclined to tackle – with a jeweler’s lupe, however. This work, a tour de force of collage, and an art historian’s little nightmare, beautifully sums up the horror vacui which pervades his work – and which is essential to the beauty of Hispano-Moorish art, still another pungent ingredient in this artist’s eccentric vision.

Finally, aficionados of New Mexico’s rich Hispanic art history may detect, as I do, a religious, almost cultish compulsion behind these strange tableaux. The painted and richly ornamented shrine is a beloved format in that venerable tradition; about such shrines, as here, there occasionally hovers the breath of immanence. It is even possible, after all, that this wonderfully peculiar work is, effectively, Carlos Quinto Kemm’s personal avenue to revelation, through art.

– 1996 Contemporary Art in New Mexico, by Jan Adlmann and Barbara McIntyre, Craftsman House in Association with G & B Arts International Publishers.