Albuquerque Journal – The Arts

The Art of the Night – Las Vegas Native Creates Elaborate Paper Collages

By William Clark

Carlos Quinto Kemm leads the way through the house where he grew up, down a flight of stairs into the basement room, filled with books and pictures, where he lives and works.

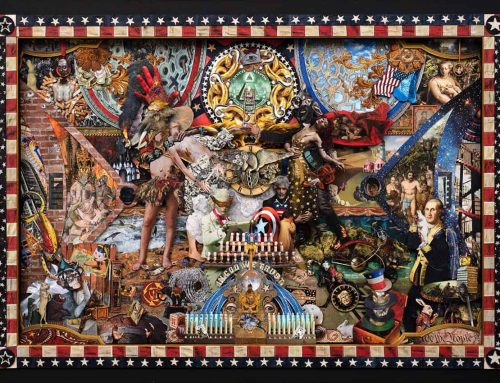

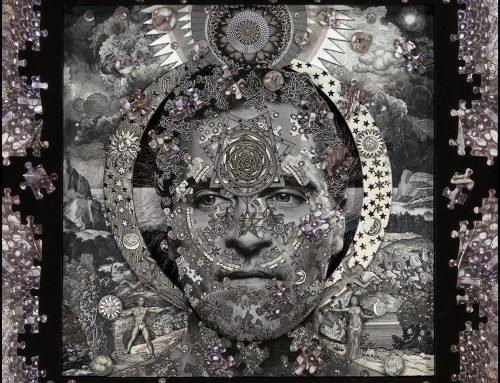

With its stone walls, this compact studio evokes the chamber of a medieval monk, a painter of icons and the strange beasts of illuminated manuscripts. Kemm’s small, meticulously assembled paper collages of a sometimes Byzantine elaboration, shimmering with luminous color and foil-like metallic paints, indeed suggest such sources, but with their surreal, often erotic imagery, they have the fin de siecle flavor of icons as Aubrey Beardsley might have made them.

The pieces of a collage in progress – a carefully scissored clown’s face glued to the figure of a man wearing a tuxedo, with a nude woman riding on his shoulders – lie in an incandescent pool of lamplight on the worktable where Kemm habitually works in the dead of night.

“I’ve always had a predilection for the nighttime hours when the world shuts down,: he says, “the quiet hours with no interruptions. There’s a wonderful stillness – just one light on, over my work – and there’s and intimacy about the night that’s very special, reserved for lovers, sleep, dreams. I’m just a night person – I work better then.”

Kemm, 37, is a Las Vegas native, was raised and educated here. During his college years, he traveled for a time, studied mural making in Mexico City, spent a year at the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque. But strong family ties drew him home and held him in Las Vegas, where he completed a bachelor’s degree in painting and philosophy at New Mexico Highlands University in 1975.

Kemm began his career as a representational, painter, but in the late ’70s, he says, “I kind of burned out with painting – something abruptly was not there – and I turned to collage. From 1980 onward it’s been scissors.”

Kemm began by collaging cut-out imagery on plates of glass, building pictures in layers to create an illusion of depth, he says, “that drew you in like a pool of water. I’m drawn to something small, intricate, where if one person looks at it , that’s all – that’s the field of view,” he says, describing the influence on his work of the Mogul miniatures of India.

“At first I just cut things out, didn’t tamper with them,” Kemm says, “but there was no sense of texture and I missed that – the feel of the paintbrush, the tactile signature.’ To protect his paper cutouts, to keep the printers ink of the pictures from running, he began coating his clippings form magazines and books with acrylic gel to create a textured, durable surface on which he could apply paints and inks.

Now, instead of stacking elements of his collages between pieces of glass, Kemm creates a more subtle illusion of depth with layers of clear gel bearing successive glazes of color. The method lends a luminous glow to his magic-realist works. His pictures evoke the world’s mythic stories, they are built around themes of love, death and resurrection and are inhabited more often than not by exotic, sensuous women.

“A good piece will resonate with all of that,” he says, “I think Freud was right when he said that the creative urge is very tied in with libidinal drives. It has to do with what makes the spiritual vital, a battle of the spirit and the senses, and I swing both ways in my work. You can’t live in pure aesthetic contemplation, intellectual isolation, without being grounded in tasting everyday life with all its frustrations, all its vitality.”

The source of Kemm’s enigmatic renderings is , he says, “the cumulative subconscious that we all share. So why not,” he asks rhetorically, “regurgitate the bombardment of visual images, stuff from magazines that we also share. It’s the flotsam and jetsam of life and in it there are jewels to be discovered, many elements to be recast, in a personal sense, into one.

“I love imagery, poetry, the gathering together of things,” Kemm says, “I think a fine poet puts together words well-chosen to give language in a very fresh, unpolluted way. In a visual sense, magazines are polluted, and I wade through them until I see an image, am struck by it, and it becomes a starting point.”

The literature of Zen Buddhism, says this former philosophy student whore interest in religion run deep, “talks about reaching a still point where you can become a conduit for deeper-than-self preoccupations. In my shuffling through papers, a vein of imagery erupts from a deeper source.”

“I don’t set out with any conscious effort to make a statement,” Kemm says with a shrug, “I just go through magazines until something clicks.”

From that revelatory spark, that visual seed, Kemm’s collages develop gradually as he combines and recombines elements in what he describes as a kind of meditative play. The results are often much more complex than they at first appear – in the face of a woman, for example, he may synthesize a head from one source with a mouth, eyes and ears from others, bits and pieces drawn from filing cabinets filled with clipped pictures.

“It’s a matter of listening to the images together, of seeing, literally, where they’re going, what placement does for them” Kemm says. “It’s like chasing something in a forest – you catch tantalizing glimpses and keep pursuing it further and further. The whole thing just grows organically until it reaches its dimension.”

With spray glue, Kemm fastens his loose assemblages to heavy rage paper, brushes on the first layer of acrylic gel, and begins coloring them with acrylics and metallic paints, oil pastels and a variety of inks. Some of Kemm’s pigments are opaque, other transparent, often wiped down to a mere trace. In both the composition of his cut-paper elements and the application of color, Kemm works intuitively, adding and subtracting until the picture suits his fancy.

In about half of his images, Kemm pushes the collage technique into a more pronounce third dimension by attaching elements ot foam-core board, trimming them out and lifting them off the picture surface on blocks. His finished pictures are usually mounted in lavishly decorated mats.

“I think I use the pieces for personal discover, to explore my own psyche,” Kemm says. These meticulous creations have no specific meaning, but are intended, he says, “to set off certain ideas, emotional triggers. All of us have a great range of emotional responses that need to be awakened and, if nothing else, I want to cause a good fantasy.”

But above all, these images offer, Kemm says, “a window on a special private universe where I’d like to live. The Garden of Eden is a recurrent image in my work, and finding that garden our personal lives is important for all of us. That can radiate to the community, making it a garden too, a place where we can trust one another with real love and respect, like angels.”