Magical Blend Collages from The Depths

By Mary Carroll Nelson

Carlos Quinto Kemm manifests dream imagery in multi-layered collages. They emerge from the subterranean reaches of his mind, literally represented by his studio-the basement of the home in which he was raised. With few exceptions, the townspeople of Las Vegas, New Mexico, are unaware of the dream master in their midst; yet Kemm’s exotic work has carried his name into the retentive psyches of many collectors.

Las Vegas, where the Kemm and Allemand families have lived for generations, is a stronghold of Hispanic Catholicism. Charles Kemm, the father, was an educated and lenient man, who allowed his son to attend public school and to roam free. Carlos recalls being mesmerized by the still water in nearby acequias (irrigation ditches) and by the crayfish crawling along the bottom of a flagstoned millpond. These visual memories has taken on a symbolic part in the myth he is in the process of creating.

At a young age Kemm became an avid reader of mythology and poetry. “I luxuriated in it,” he says. At seventeen he bought a paperback copy of Carl Jung’s Man and His Symbols and “devoured it.”

At his alma mater, Highlands University in Las Vegas and the University of New Mexico, he consumed books, but he did most of his artwork outside of class. When he brought it in for critique, his mentor at Highlands, Elmer (Skinny) Schooley, urged him on. It was Schooley, a revered, now retired teacher who recognized that Kemm had truly found himself as a postgraduate when he first turned to cut paper collage.

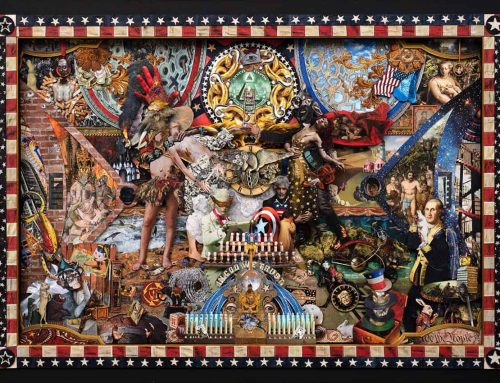

Even then, one of his main themes was Woman in all her aspects. Kemm’s compositions are paeans to the Goddess. In his chosen isolation, he is an acolyte serving the returning feminine divine nature. His heroines are Circe, Venus and Chantico, the Aztec Fire goddess (Kemm traveled and studied in Mexico for a year), but Kemm also portrays the hag. Locked in by her narrow mind, a grotesque elderly woman with a perfect apple on her head is portrayed in “Aim of Censorship.” Within this horrific piece, Kemm added a soaring butterfly. He often projects the dilemmas of humanity in a mythical context, but in every one there is a ray of hope.

Kemm’s chosen art form is the collage. Collage is derived from the French work “coller,” meaning to glue. The medium allows the collage artist the freedom to use anything that furthers his goal in creating an image. Therefore, collage is appropriate to out end-of-the-century period, marked by the breakdown of categories and the emergence of a new paradigm based on synthesis and holism. In their book, Creative Collage Techniques, Leland and Williams observe, “Collage as an art form is uniquely a twentieth century phenomenon, with the capacity to dominate visual art in the twenty-first century.”

Kemm believes, “Anything is possible in a collage. It is a true adventure to recast commonplace materials, fragments of something that arrests me, and transform them. In such a throw-away culture, we have images in abundant supply. I have discovered that fate will bring me the image I need.”

Kemm creates complex paradoxes by patiently arranging fragments of found imagery, often taken from the history of art. Fine art magazines provide his palette. A challenge of his work is to search for a recognizable image-perhaps a bit of Watteau’s clown or Thomas Hart Benton’s reclining Persephone-embedded in one of his allegories.

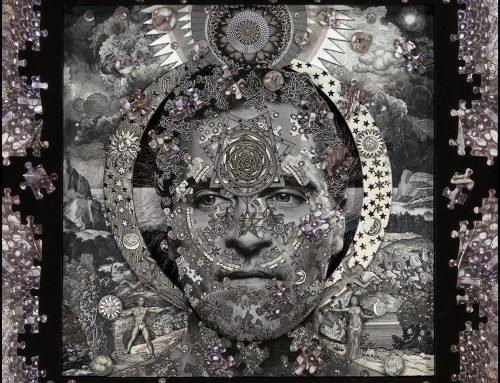

Like a director placing his characters at various parts of a stage, Kemm builds a composition from the deepest layers to the surface, by mounting pieces on pillars of varying heights. The depths signify distance in both time and space.

Were creating a collage all he does, Kemm would still be an exciting artist, but he goes much further than that. His work is not complete until he embellishes its surface, and usually the border, with a screen of jewel-like dots, made patiently with a brush. Kemm’s dots identify his work, while serving as an overlay of swirling energy between the collage and the viewer.

Until he is well into a piece, Kemm does not know entirely what it means. “Each piece is a meditation,” he explains. “I don’t set out to create a specific image, but I become aware that my work is telling a story. My attitude is in the Zen tradition of the empty vessel. I’ve been trying to live Zen a number of years. Zen is an attunement to simplicity. Simplicity, for me, is a state of meditative awareness and openness.”

While in such a state, Kemm created “La Leyenda de La Luz” (Legend of the Light). “Afterwards, I saw it is like Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave.” We all live in an illusion. The cave is a symbol of our enclosed ignorance. The male is a caricature with a monocle, myopic in the stance of a warrior. The female wears rose-colored glasses. The feast set before then resonates for me. It is divided among male and female elements. The pig has a man’s face, peering out through its side where it has been cut open. A praying mantis eats a tiny human arm. The marionette symbolizes rising above pain. While it is being manipulated, it also holds scissors and a wounded heart. Behind the clown is blue Plexiglas, like a deep pool of water. I added a figure to Magritte’s famous bottle. He is leaping to his death through the clouds. The work is a symbol of the unknown and has a feeling of alcoholism, the suicide of one’s self.

“I asked myself, where is this going? In the cave, what was there at each level? Crumbling walls of golden bricks imprison the couple in their greed. Below are Lazurus wrapped as a mummy and Death, from a Tarot card. Past him is the rebirth, the resurrection. Farthest back, the center of the cave opens up. There is a stream with a boat and a little light. To find the light and escape the cave, there is a way out. It takes courage.”

Kemm applies the words “emergence” and “submergence” to his work, and they are equally relevant to his life. He is both of, and removed from, the life of those around him in Las Vegas. His patient dot-making and precise cutwork are links between himself and the craft traditions of his neighbors, who do colcha embroidery, weaving, straw inlay and pierced tinwork. However, Kemm does not portray his early life as a Hispanic boy in a semi-rural neighborhood. Rather, his allusions are to the world of literature, imagination, fine art and the haut monde. Standing before “The Garden of Earthly Delights” at the Prado in Madrid, Kemm found a resonance with Hieronymus Bosch’s imagination. Of this painting, Janson said its panes “are so densely filled with detail that their full beauty and imaginative power can be grasped only at close range. The entire work demands to be ‘read’ slowly, like a long religious poem…” He might have been writing about a Kemm.

A glimpse of another dimension can happen in New Mexico as easily as it can in sixteenth century Holland. Kemm’s imagination was fueled in part by the stories of the paranormal that he heard from his mother and father. Fernanda Allemand Kemm told him of the time when she and here brother were children riding a buggy into Las Vegas from the family ranch. Suddenly they saw a farol, a little light, swinging back and forth in the distance. As they crossed and arroyo, this light leapt over the ditch showering sparks. Charles Kemm related the tale from his great uncle Juan, who spoke of seeing spirits disguised as fireballs. These elementals could be questioned only by a person named Juan or Juana. If that person put on clothes backward and drew a circle on the ground, the spirit would be compelled to enter the circle and answer questions. A few such tales can pierce the illusion that visual reality is all there is , and these notions stay in one’s mind forever.

A lean man with a luxuriant crop of black, slightly graying curls surrounding a face in which every bone seems visible, Kemm might easily fill the role of a medieval Franciscan friar, Talmudic scholar or Chopin. He makes a fine model for a player in one of his own images that evoke the magical world of inner sanctums-those hermetic places where secrets are kept.

Though reserved, Kemm is also responsive. In repartee, he is disarmingly forthcoming. He describes himself in the language of Mexican spiritual traditions, “I am a dreamer, not a stalker. Stalkers are engaged with everyday life. A friend of mine told me that a professional artist who is a stalker would prepare portfolios and make appointments with galleries. As a dreamer, I visualize openings while in a meditative state, and they usually happen.

“Dreams are the source of my work. I’ve always had a strong dream life, and i opened my consciousness to reach those life changing dreams that haunt me. One of my dreams was of a cliff scene. I saw lightning turn into seagulls. When I created the image, I incorporated the seagulls into the lightning with a photo fragment of nuns, in white habits, riding their bicycles. Their wimples looked like gulls.”

“I’m glad for my inclinations. Everything is tolerable. When you pay acute attention to the moment, that’s when Epiphanies happen. Art becomes a personal diary. My pains and growth are alchemized in my work.”

“In Zen, the world around us is a meditation. This plane of existence is cocreative with God, with every possibility for transformation to other planes of advancement. Within, I am on a search for God. I hope for communion with God-essence where everyone is open. A new myth is coming to fill the wasteland of the spirit and give it a reinterpretation. It is right there waiting to feed our thirst. In American culture, people are awakening to that hunger. The role of the artist is partly to celebrate and partly to awaken awe and a sense of mystery. A whole new frontier is opening.”

“I have no doubt there are better places than this one, but the magic is in seeing the incredible beauty we have right here before us.

– 1995 Magical Blend Magazine, “Collages from the Depths – Carlos Quinto Kemm”. Feature article by Mary Carroll Nelson. May/June/July issue.